On the afternoon of May 9, 2022, the Atlanta police were all over this fancy mansion owned by Jeffery Williams, the rapper Young Thug. There were more than a dozen buddies hanging out with Williams at his place, on a quiet street in Buckhead, an area of Atlanta where new money mixes awkwardly with old. One neighbor spotted three armored SWAT trucks and a bunch of cops on foot, all storming in with lights and megaphones. From what it looked like inside, the authorities had busted up a beer pong game. And guess what? There were some THC-infused drinks in the mix. It was like the parents had left for the weekend, according to Doug Weinstein, a lawyer for one of the dudes at the house. The mansion had an Icee machine, paintings of musical icons like Prince, Kurt Cobain, and Janelle Monáe, and a huge glass wall that let Williams, as he said on social media, “just look at clouds and, you know, trees.” He was sporting a white Harley-Davidson tank top and a chill expression as he got taken away in cuffs. He left behind a pink Lamborghini and a bunch of bling, including a $1.7 million Richard Mille watch that some folks later claimed to see on a cop who testified against Williams in court. (The Atlanta police denied swiping anything from the house.)

Williams grew up twelve miles south, in an Atlanta housing project that no longer stands. He had ten siblings, one of whom got shot and killed right in front of their family home when Williams was just nine. Another sibling ended up behind bars. Williams, the second youngest, broke a teacher’s arm back in eighth grade during an argument. That landed him in juvenile detention, where he dabbled in music and, as he put it later to Rolling Stone, enjoyed “gambling, smoking, and, you know, fooling around.” He dropped his first mixtape, “I Came from Nothing,” in 2011 when he was nineteen. Rapper Gucci Mane signed him, and soon he was collaborating with big names like Justin Bieber and Kanye West. By his late twenties, Williams had become a chart-topper and Grammy winner, hailed by the BBC as “the 21st Century’s most influential rapper.” He played a key role in pioneering “mumble rap,” a laid-back and melodic style of trap music, and he embraced an androgynous look. Sometimes he rocked little girl’s clothes, painted his nails, and called his male pals “babe.” On the cover of a 2016 album, he sported a billowy periwinkle dress from Italian designer Alessandro Trincone, which he said reminded him of a character from Mortal Kombat. He later rapped, “Had to wear the dress ’cause I had a stick,” which we can only guess refers to a gun. Up until 2022, Williams had no adult convictions, but his songs often mentioned illegal stuff, along with guns and drugs, both of which were found in his Buckhead home.

At the time of Williams’s arrest, Fani Willis, the Fulton County district attorney, was still pretty new in her first term, and she was swinging for the fences. She was also going after Donald Trump in an election-interference case, using a strategy originally aimed at curbing Mafia activity: the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, which holds every member of an alleged conspiracy accountable for everyone else’s crimes. Georgia’s RICO statute, created back in 1980, is pretty wide-reaching. In 2013, Willis had used it to charge over a hundred and seventy Atlanta public-school educators whom she accused of systematically changing answers on their students’ standardized tests. Some of them even had “changing parties.” Eleven folks ended up convicted. “I’m all in on using RICO,” Willis later said.

In 2016, Williams set up a record label called Y.S.L., short for Young Stoner Life, a nod to Yves Saint Laurent. (Williams used to rock high-end labels in his youth and was called “the king of white-boy swaggin’.”) Willis claimed that Y.S.L. was actually a violent gang known as Young Slime Life, led by Williams, a.k.a. King Slime, and tied to the Bloods. Her office put together a slideshow detailing an escalating gang war between Y.S.L. and another local Bloods faction. It featured tons of pictures, many swiped from Instagram, of young Black men, including Williams (whose first name was spelled wrong on lots of slides). The guys posed with cash stacks, flipped the bird, brandished machine guns, peeked through blinds, leaned on cars, flaunted bling and tattoos.

Williams has six kids. “One of them sings, one of them raps,” he shared. “I tell all of them to become lawyers.”

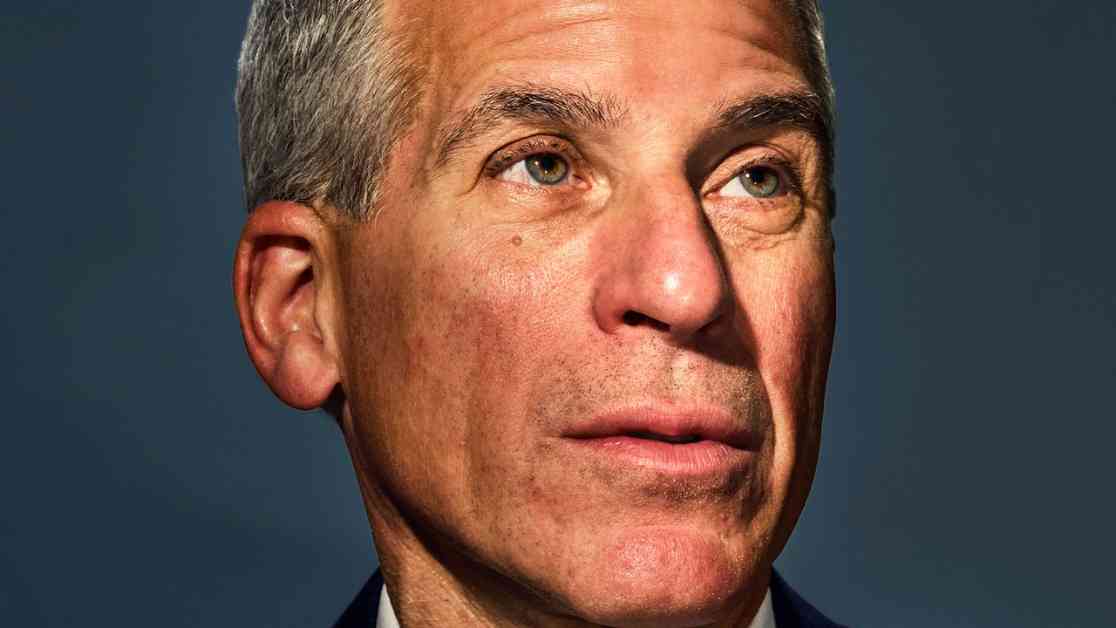

Photograph by TNS / ABACA / Reuters

The prosecution argued that Williams was running a Mafia-like crew where underlings did his dirty work. Twenty-eight people were indicted on fifty-six charges, including armed robbery and carjacking. One man supposedly shot at rapper Lil Wayne’s tour bus, Williams’s idol turned rival. Another was accused of “seriously disfiguring the buttocks” of a woman with a rifle. Williams himself supposedly made “terroristic threats” to a mall cop. Amid all this, an unsolved murder stood out. In January 2015, a guy named Donovan (Peanut) Thomas, twenty-six, got killed in a drive-by shooting outside a barbershop in downtown Atlanta. During questioning, Kenneth (Lil Woody) Copeland, a Y.S.L. associate with a rap sheet, hinted that Williams was involved. Rumors flew that Thomas’s last words were “Thug had me killed.”

Williams denied the accusations and awaited his trial in Cobb County jail. He was kept solo in a concrete room with a bed, a toilet, and a light that never turned off. At one point, from jail, Williams rapped to a nephew by phone. “I tried to cry, but ain’t nothing left—yeah,” he said. “I contemplated doing myself in—yeah. . . . But let’s not forget that this ain’t Hell.” His only visitors were his longtime lawyer, Brian Steel, a fifty-nine-year-old Queens native. The two did pushups and prepped for what would become the state’s lengthiest criminal trial.

Until recently, Brian Steel’s rep was more local news, known mainly to his Georgia peers. But that started to change with the Williams case. This month, it takes on a new chapter: Steel will defend Sean Combs, the music mogul and former billionaire known as Diddy, who’s facing charges of sex trafficking, racketeering, and assorted violent crimes. The allegations have drawn comparisons to Bill Cosby, R. Kelly, and Jeffrey Epstein. Combs is waiting for trial in a Brooklyn detention center, with access to TV, Ping-Pong, yoga mats, and, up until a few weeks ago, Sam Bankman-Fried’s company. (“He’s been kind,” Bankman-Fried told Tucker Carlson.) Whatever the outcome, the trial will further raise Steel’s profile. Williams, now thirty-three, has six children. “One of them sings, one of them raps,” he said. “I tell all of them to become lawyers.”

If you’re in trouble in Georgia and can splash the cash for a top-notch defense, who do you hire? Well, there’s Drew Findling, the so-called “billion-dollar lawyer” with a quarter of a million Instagram followers, who’s repped rappers like Gucci Mane and Offset, and has been likened to “Robin Hood with Jesus swag.” Or you could try Bruce Harvey, the High Times-reading, memorably profane barrister once called “Atlanta’s foremost long-haired, left-handed, anti-establishment liberal lawyer.” (His business cards scream: “STOP TALKING.”) There’s also Steve Sadow, a belligerent, cowboy-booted attorney who’s repping Trump in his Georgia election-interference case. And then there’s Brian Steel, whose only flashy feature is his surname. Steel isn’t on Instagram, doesn’t rock a ponytail, and doesn’t drive a Porsche with an “ACQUIT” license plate like Harvey once did. He seems more like a tax guy, which he almost was, and he rolls in an electric car painted off-white, stocked with fruit and water for whoever needs it.

“Brian doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, and can’t believe anybody would,” David Botts, an Atlanta defense attorney who’s known Steel for three decades, told me. “He won’t curse, even in court—even if he’s reading from a transcript. So when he’s cross-examining he’ll say, ‘So-and-so F-word.’ The court will say, ‘Mr. Steel, you can read that word.’ But Brian still won’t do it.” Botts went on, “Brian only drinks water. His lunch is tofu or salmon, maybe, and a salad. No bread. I’ve never seen him eat out. And he’ll bring a toothbrush to court. A toothbrush! He exercises daily, before or after court. Running. Swimming. Weights. And he’s got a great family—three kids, a wonderful wife, Colette, who is also his law partner. They kind of idolize each other.”

When reading alphabetized documents in court, Steel will reach the third letter: “C,” he’ll say, “as in ‘Colette.’ ” Steel has other quirks: he superstitiously kisses a finger or taps a table any time death is mentioned. He peppers tragic sentences with “God forbid.” He prefaces the names of everyone in court with “the Honorable.” Reporters are “Mr. Journalist.” A prominent judge said that Steel’s formality is “bordering on unctuousness,” but he was inclined to believe that Steel, whom he’d once seen cry in court, really means it.

Steel’s kids described a man of almost unbelievable purity. “I get a text every single morning,” Jake, his adult son, told me. “He’ll say: Place a smile upon your face. Look forward to the opportunities. Laugh. Be compassionate, prepared, focussed, determined, organized, energized, well rested. I believe in you. Enjoy every day. I love you so much.” Young Thug’s mother now gets a text, too. Jake’s sister Alisa compared her dad to Morrie Schwartz, the titular Morrie in the book “Tuesdays with Morrie.” Morrie, however, probably couldn’t have bench-pressed three hundred and twenty-five pounds, as Steel, who is five feet nine, once did. These days, he runs marathons. “We gave him a marathon-medal holder that says ‘Man of Steel,’ ” Bari, his other daughter, told me.

Scott McAfee, the superior-court judge who is presiding over the election-interference case, recalled a slide show that was shown at a recent meeting with two hundred of his colleagues. The first slide was about avoiding the kinds of errors that lead to an appeal. “The next one was: What happens if you don’t do this?” McAfee told me. “And it just had a picture of Brian Steel’s smiling face.” Javaris Crittenton, a former N.B.A. player whom Steel defended against a murder charge, told me, “It’s almost like an angelic sound when he speaks. It’s all eyes focussed on him. He has a halo over his head.” By the time I reached Danny Corsun, one of Steel’s childhood friends, his canonization seemed nearly complete. “Brian would call my mother every year to thank her for giving me to him,” he said. “My mother lived for those phone calls.”

Steel was born in 1965; he described his childhood as “utopia,” and then mentioned getting beat up. (He eventually ended the hostilities by landing a blow with a heavy textbook.) His sunny outlook was rooted in perspective. When he was a teen-ager, his father, an accountant, took him to a Lower East Side tenement similar to the one where his great-grandparents had lived after fleeing Eastern Europe. “It was a room with no water, no kitchen, no bathroom,” Steel told me. “My great-grandmother couldn’t read or write. They worked at seltzer factories where people lost fingers.” His father told him, “You may sweep the streets of Manhattan, but your streets will be the most talked about.”

Steel went to Fordham Law, then became a tax attorney with Price Waterhouse. The job paid well, but he was distracted. A Fordham professor had allowed him to assist in the retrial of a young man who had been convicted, at thirteen, of choking another boy to death. “He was found guilty again, and I couldn’t believe it,” Steel told me. “I’ll go to my grave believing he was innocent.” Corporate-restructuring deals, by comparison, felt pointless. In 1991, he took an internship with the Fulton County Public Defender Office. Shandor Badaruddin, who started there around the same time, said, of Steel’s approach to clients, “He was pretty sure they were all innocent.”

In 1992, Steel was assigned the case of Greg Shephard, an illiterate man charged with the attempted murder of an Atlanta railway officer. “It’s a dead-bang loser,” Steel recalled a colleague telling him. “You need to understand what losing is about.” Steel met with Shephard, but the man wouldn’t talk. So Steel slept in the jail with him, and Shephard slowly opened up. He was innocent, he eventually said. After his arrest, police brought witnesses by, and the witnesses said, “It’s not him.” Shephard recalled that one of them had worn a fast-food uniform. “I subpoenaed everybody working at fast-food restaurants within five miles,” Steel told me. He remembers eventually reaching a woman who had seen the attempted killing, and she said that Shephard was not the shooter. Other witnesses backed up her assertion. “Our agreement was: if we get him home, he has to learn to read and write,” Steel told me. Shephard eventually landed a job with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s distribution department. “He used to come to my office every Thursday,” Steel told me. “And he’d read to me.”

While arguing a case in court, Steel sometimes feels a kind of moral ecstasy. “A fair trial is better than sex,” he told me. (“I wouldn’t go that far,” Keith Adams, a lawyer who works with Steel, said.) Steel added, “And then you see witnesses told to lie. Evidence hidden. People unprepared, misquoting law, violating rights. That’s when it’s outrageous.” Steel’s attitude can buoy his clients. Crittenton, the former N.B.A. player, was released from prison in 2023, after serving eight years for accidentally killing a woman with a bullet aimed at a man who, he said, had robbed him. Steel had got the murder charge reduced to manslaughter. “When I took the plea deal, Brian said, ‘I’ll never leave you,’ ” Crittenton told me. “He kept his word.” At one point, Crittenton said that he was being mistreated in prison. Steel, who was no longer being paid, sent letters and contacted the warden. During one prison visit, a corrections officer told Crittenton to put his face against the wall of an elevator. Steel turned around and did the same. “That meant so much to me,” Crittenton said.

In December of 2022, Sergio Kitchens, one of Williams’s co-defendants in the Y.S.L. case, saw a way out. Kitchens, who raps under the name Gunna, entered what’s called an Alford plea, which allowed him to plead guilty to a single RICO charge while maintaining his innocence. In the process, he agreed to a series of statements, including “Y.S.L. is a music label and a gang and you have personal knowledge that members or associates of Y.S.L. have committed crimes in furtherance of the gang.” Later, though, Kitchens released a more nuanced statement of his own. “When I became affiliated with YSL in 2016, I did not consider it a ‘gang’; more like a group of people from metro Atlanta who had common interests and artistic aspirations,” Kitchens wrote. “My focus of YSL was entertainment—rap artists who wrote and performed music that exaggerated and ‘glorified’ urban life in the Black community.”

There is no single definition of what constitutes a gang. Alex Alonso, a gang researcher in Los Angeles, told me that, although Black street gangs are often associated with criminality, estimates suggest that only around fifteen per cent of gang members are actually involved in violent crime. Most join, instead, for a sense of community and protection. In the seventies and eighties, the Gangster Disciples, a large Black gang that originated on Chicago’s South Side, had a hierarchical structure, national reach, and strict operational procedures. But in the nineties, at the height of the crack epidemic, federal authorities jailed many of its leaders. Lance Williams, a professor at Northeastern Illinois University, said that there are now hundreds of local groups that go by acronyms—Only My Family (O.M.F.), Four Pockets Full (4.P.F.)—and may claim association with national gangs. But the associations are largely superficial. They wear specific colors, or release songs with lyrics using certain slang, to “fit the narrative and the culture,” he told me. Some members may indeed commit crimes. But these crimes are generally interpersonal, rather than orchestrated by the group.

The RICO Act was used to target the Mob, which coördinated its crimes. But holding members of loosely connected local gangs responsible for one another’s actions can feel like overreach. Alonso put me in touch with Ronald Chatman, a onetime member of a Bloods subset in L.A. who subsequently worked in the Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development. “You’ve got a lot of dead fathers, a lot of fathers in prison,” he told me. “The kids is being raised in the streets.” Chatman has a podcast that sometimes touches on gang life, and had offered advice, “as an O.G.,” to young gang members in Georgia who had found him on social media. In 2020, Chatman was charged in a RICO conspiracy in the state, and accused of “making organizational decisions regarding the expansion” of the Georgia gang. (The indictment notes a YouTube video in which Chatman “did discuss rivalries and territory.”) Chatman took a plea deal to avoid a trial in a rural white county. “He was not a mastermind of any gang in Georgia,” Alonso insisted. “He was a generous former gang member with a podcast.”

This kind of ambiguity lay at the heart of the Y.S.L. trial. Prosecutors pointed out that, on social media, Y.S.L. affiliates often wore red, a Bloods’ color. Some used the expression “BLATT”—as prosecutors defined it, “Blood Love All the Time.” In one post, they argued, Williams appears to flash a gang sign. In another, he seems to threaten a witness of some crime who is planning on testifying: “So a nigga lie to they momma, lie to they kids, lie to they brothers and sisters, then